Peter Mandelson’s Leaking of Secrets to Jeffrey Epstein Betrayed Gordon Brown, the Labour Party, and His Country

The former UK prime minister is on the warpath against ‘the prince of darkness,’ whom the current UK prime minister made a disastrous bet on. The police are now getting involved, too.

It is no wonder that the former British prime minister, Gordon Brown, told a friend last fall: “Peter Mandelson is a very bad person.”

We now – if we even really needed one – have an extra reason why. Mandelson is all over the Epstein files. Not just shopping with his “best pal” Jeffrey Epstein in St Barths, being photographed in his underwear with an unnamed woman, or securing thousands of pounds in payments from the pedophile financier for his husband Reinaldo Avila da Silva.

But stabbing a sitting prime minister – Gordon Brown, his friend, his patron, his boss – in the back.

First, some background for the uninitiated: Peter Mandelson is one of the most consequential and controversial figures in modern British political history. Nicknamed the ‘Prince of Darkness,’ Mandelson, alongside Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, was one of the architects of the New Labour government that was in office from 1997 to 2010, and that transformed British government and politics forever.

As I document in my new biography of Gordon Brown, the then-Labour Party communications chief Mandelson “made” the up-and-coming politician Brown a prominent public figure in the 1980s and 1990s by promoting him on the airwaves while “excluding” others. They fell out spectacularly in 1994, when Brown felt Mandelson was duplicitous in backing Blair for the Labour leadership following the death of the then-leader, John Smith. Decades later, Brown “rehabilitated” a disgraced Mandelson, elevating him to the House of Lords as Baron Mandelson of Foy in 2008, and bringing him back into government as the business secretary. Before today, Mandelson had a unique record of having been forced to resign in disgrace from the British government on three different occasions over the course of 27 years: first in 1998 (as Trade and Industry Secretary), then in 2001 (as Northern Ireland Secretary), and, most recently, in 2025 (as British ambassador to the United States). His political career consists of one eye-opening comeback after another.

Not this time.

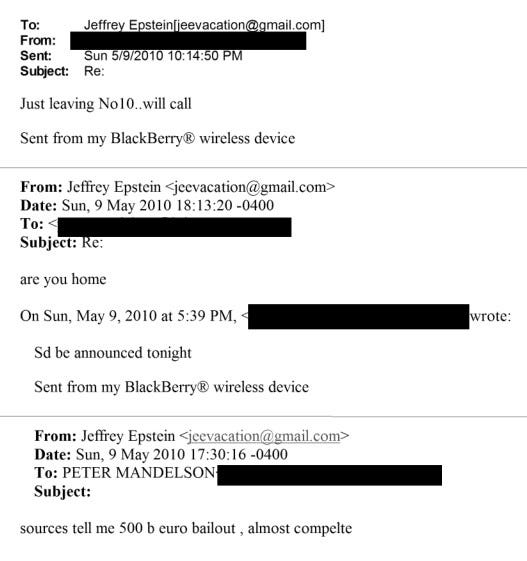

Friday’s disclosures from the Department of Justice’s Epstein files dump appear to show Mandelson habitually sent multiple emails to the late sex offender and financier, leaking sensitive and confidential information about the British government’s handling of the global financial crisis while he was serving as business secretary under Gordon Brown.

On Sunday night, Mandelson announced he was resigning from the Labour Party, saying he did not want to cause “further embarrassment” to the party. But by Monday night, the veteran political commentator, Will Hutton, said “the Mandelson affair ranks as the greatest political scandal of the last sixty years.”

Today, the House of Lords speaker announced Mandelson would retire from the upper chamber effective Wednesday.

Betraying Brown

By September of last year, Gordon Brown knew or at least suspected something about his former business secretary’s leaks to Jeffrey Epstein. The former prime minister asked Chris Wormald, the cabinet secretary, to examine communications about the sale of assets between Mandelson and Epstein. Brown has said he was told “no departmental record could be found.” This is hardly surprising, given we now know Mandelson was using his private email account to leak market-sensitive information to Epstein. As one senior Whitehall source told me on Monday night: “If he had been a mere civil servant, he would have had his fucking door kicked in by now.”

One email, with the subject line “Business issues,” that was sent by Brown’s special adviser Nick Butler on June 13, 2009, was forwarded by Mandelson to Epstein that very same day with the line: “Interesting note that’s gone to the PM.” Butler was among several figures from across the political spectrum on Monday who suggested this and other leaks were a matter for the police, who are now reviewing reports of alleged misconduct in public office by Mandelson to see if they warrant a criminal investigation.

Mandelson also suggested to Epstein that the JP Morgan boss Jamie Dimon should “mildly threaten” the then-British Chancellor Alistair Darling over a proposed bankers’ bonus tax.

And he gave advance warning to Epstein of a €500 billion bailout the EU planned to save the Euro – literally the night before it was publicly announced.

It is difficult to think of a precedent for this kind of stunning, some would say “treacherous,” behavior. Gordon Brown issued a scathing statement on Monday: “Given the shocking new information that has come to light in the latest tranche of Epstein papers, including information about the transfer to Mr Epstein of at least one highly sensitive government document as well as other highly confidential information, I have now written to ask for a wider and more intensive inquiry to take place into the wholly unacceptable disclosure of government papers and information during the period when the country was battling the global financial crisis.”

From Mandelson to McSweeney

The pressure is now on Brown’s successor as Labour prime minister, the current incumbent Sir Keir Starmer, who called for Mandelson to be stripped of his peerage. Yet Starmer’s own judgement and that of his influential chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, have to be called into question. It was Starmer who heaped praise on Mandelson as he appointed him as envoy to Trump’s America in December 2024, saying he was “delighted” to appoint someone with such “unrivalled experience” to the role. And it was McSweeney who recommended his mentor Mandelson for the job of British ambassador to the US, and then reportedly pushed to keep him in his DC post even after revelations about the depth of Mandelson’s ties to Epstein were revealed last September.

There was a point at which Mandelson and McSweeney were reportedly speaking to one another every single day. And Mandelson is on record saying, about his protégé in the dark arts of spin: “I don’t know who and how and when he was invented, but whoever it was, they will find their place in heaven.”

Starmer’s reliance on McSweeney is, of course, reminiscent of Tony Blair’s reliance on Mandelson. Starmer himself initially seemed to model himself on Blair (without the flair) but perhaps he should have learned a few lessons from Brown instead. (“Not flash, Just Gordon,” was a resonant advertising slogan deployed by supporters of the then prime minister back in 2007.)

At this point, a disclaimer. My new biography has already been attacked in the right-wing Daily Telegraph as “far too complimentary” about Brown. In fact, it is independent, unauthorized, and unapproved. It contains criticisms of Brown throughout, from the prologue, which calls him obstructive, difficult and needlessly suspicious of perceived opponents, to the conclusion, which notes his questionable judgement when it comes to some of the individuals he included in his own inner circle; his well-documented temper (though I must say I personally have never witnessed it); and the way in which he courted a Rupert Murdoch-owned media empire whose values were diametrically opposed to his own.

But compared to Starmer, who is relatively new to the Labour movement, and seems to lack both style and substance, Brown was and is a political titan – or to quote his fellow former Labour leader Neil Kinnock, “a poet among politicians” who has “all the kit.” Though he was reluctant to admit it at the time, Brown’s period at the Treasury was the most redistributive since World War Two. As the longest-serving chancellor of the Exchequer, between 1997 and 2007, since William Gladstone, he almost halved child poverty and oversaw record growth and investment in public services, including in healthcare. As prime minister, he acknowledged to me in my book that he made a “mistake” by not calling a “snap” election in the fall of 2007 to gain his own popular mandate after succeeding Blair. But then, the very next year, he “saved the world financial system,” to use the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman’s October 2008 description of Brown during the 2008 crash. And it wasn’t just Krugman: when then French President Nicolas Sarkozy said in a panic at a November 2008 G20 summit, “No one has a plan”, then US President Barack Obama responded: “Gordon has a plan”.

Does Keir Have A Plan?

Yet have Starmer and his own chancellor, Rachel Reeves, learned the lessons of that financial crash? In July 2025, Reeves told delighted bankers at her Mansion House speech that regulation had “gone too far.” Then there was the iniquitous Tory-imposed two-child benefit cap that punished kids living in poverty, which Starmer belatedly agreed to axe only in November of last year and after constant pressure from… Gordon Brown.

Perhaps more importantly, have Starmer, McSweeney, and the current Labour government learned lessons from the Blair and Brown era of Middle East wars? Brown now regrets supporting the illegal Iraq invasion, says he was “misled” on the issue of WMDs, and praises the late former foreign secretary Robin Cook, who opposed it. “Robin Cook was right, and I was wrong,” Brown now says. Yet Starmer sounds more and more hawkish on the Middle East, and now seems to be in support of a possible Donald Trump-led regime change war in Iran.

So what is it that the Mandelsons, Starmers, and McSweeneys of this world have in common? They lack convictions. They seem to want power for power’s sake. They have no real moral compass. Gordon Brown, for all his many flaws, was a conviction politician. Even his most diehard critics agree. Brown, first as chancellor and then as prime minister, tried to use power for a purpose. Plagued by scandals, of which this Mandelson-Epstein controversy is just the latest, and with crucial local elections coming up in May, Starmer – unless he finally discovers how to use his power for a purpose – may well find he doesn’t have any left.

James Macintyre is the author of Gordon Brown: Power with Purpose, which will be published by Bloomsbury on February 12, 2026. He is the co-author, with Zeteo’s editor-in-chief Mehdi Hasan, of Ed: The Milibands and the Making of a Labour Leader (BiteBack).

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Zeteo.

Check out more from Zeteo: