The Day I Knew Israel’s ‘Aggression’ Had Turned Into a Full-Blown Genocide

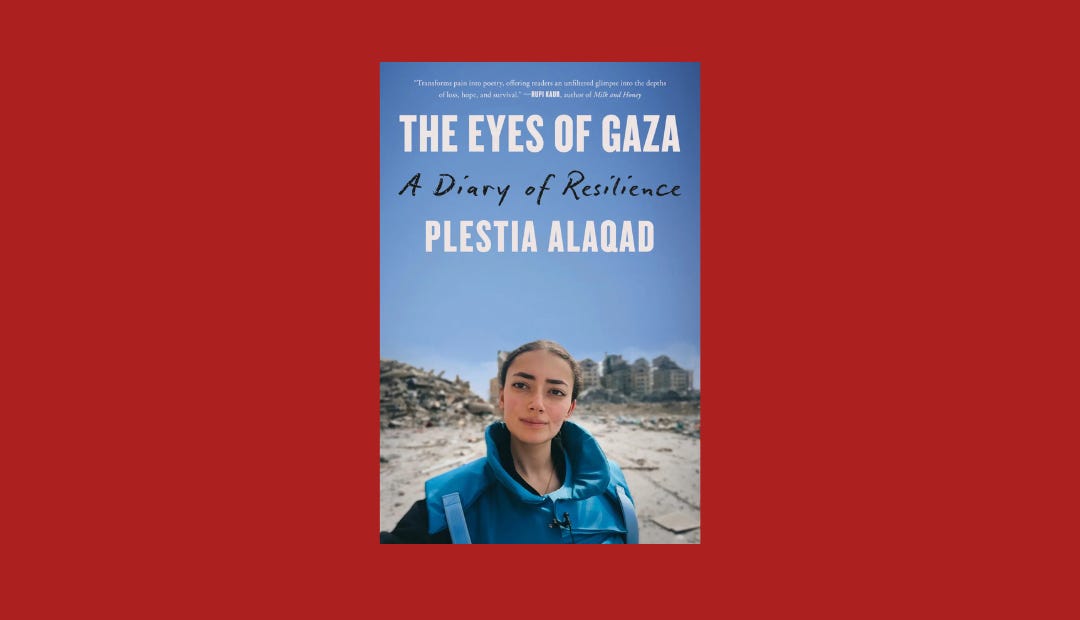

Read an excerpt from Gaza journalist Plestia Alaqad’s powerful new memoir, ‘The Eyes of Gaza: A Diary of Resilience.’

Day 12 | WEDNESDAY 18 OCTOBER

I wake up and it isn’t all over.

Today, the ‘war’ ended. This isn’t an Aggression anymore; it’s a Genocide. There isn’t another word that can describe the scale of violence I see in front of me.

I start the day at Al-Maamdani, which was bombed yesterday. Yet another healthcare facility, yet another critical service for human survival, destroyed by the IOF. I can see where the missile landed. It’s obvious. I can see all the damage, the broken glass of the windows strewn across the courtyard, the cars that are burned out and abandoned. I see other journalists holding back tears and taking deep breaths, trying to compose themselves before gathering up the power to film their reports. I see people who were witness to the massacre yesterday; I wish I could say that they’re empty shells, that they’ve been afforded even the luxury of being in a state of shock, but they’re not. They’re practical, and broken, and they’re here to look for their stuff.

There’s a church here. People’s belongings are still where they left them. I see a sandwich on the floor, with just one bite taken out of it, and my thoughts fly to the person who was eating it. They were a displaced civilian, camping out in the church of a hospital, hungry and trying to survive. And at best, they had to flee when the bombing started, forced to respond to their fear before their starvation. Maybe they later died, hungry and left for dust by the rest of the world – a world that still stands by, complacent, allowing the Israelis to get away with Genocide.

Because that’s what it is now. The world can’t pretend that there are two sides here anymore. There is no humanity, no equity, no semblance of justice. It’s a calculated, deliberate, and ruthless ethnic cleansing, and nobody seems to care enough.

Why do we live in a world where Genocide has been normalized? I spot a baby bottle in the church, under the rubble, full of milk. What happened to that baby? And its parents, what did they tell her? That this is what a thunderstorm sounds like?

Yesterday, there were hundreds of displaced people taking shelter in this courtyard. They had nowhere else to go, and they thought that a hospital would be the safest place. Imagine yourself in their shoes. You’re displaced, living in a tent in a yard, and, with no notice, Israel fires a missile directly at you. Most of the time, they strike you with a drone, a machine from afar, branded with a US arms dealer’s logo. And then you either die, or live to see others murdered and mutilated, with amputated limbs. And that’s your life.

***

I go to Al-Shifa [Hospital] next; it’s overcrowded too, with the displaced and injured strewn around like wreckage from a ship, floating wherever they can find any kind of buoyancy. I enter the hospital searching for Dr. Ghassan [Abu-Sittah]. To my relief, I’ve found out that he is unharmed, and I’m here to interview him as an eyewitness to yesterday’s massacre.

Everything is starting to trigger a cascade of emotions in me. There are items of clothing hanging on bannisters around the hospital, and I begin to imagine the story behind each one. I see a little purple dress, and I think of how, at one time, it was probably a little girl’s Eid outfit, to be worn on happy days, and how it’s now her displacement uniform. I see a man’s formal shirt – maybe that was her dad’s work outfit, and maybe he’s dead now.

The voice of my colleague, Mohamed, interrupts my imagination. ‘We’ve arrived. Dr. Ghassan is inside this room.’ I’m nervous – what am I supposed to ask a doctor who’s been [an] eyewitness to a massacre inside a hospital? – but he immediately puts me at ease. Despite the layers of trauma visible through his eyes, he has the ability to make a person feel comfortable without saying a word. The interview proceeds; it’s sad, but it comes off without a hitch.

After the interview wraps up, I decide that I can’t live with the itchiness of my rash forever, so I ask him for his advice. He tells me that it is just my anxiety showing on my face, and he gives me a cream. I feel a bit bad asking Dr. Ghassan – a man who is dealing with amputee and wounded children on a daily basis at the time – about a minor skin condition. But he doesn’t seem to mind. I guess we both need a distraction after a conversation about how to go about finding kids’ amputated limbs in a bombed-out courtyard.

Afterwards, Mohamed, Hatem [another journalist], and I go searching for some food and an internet connection to upload our work. Outside isn’t much better than inside. People are trying to go about their daily lives. In a Genocide, that means just trying to survive and salvage whatever you can. There’s a long queue of people lined up behind a well, trying to fill their water canisters. There’s a man in his 40s standing in the street with some clothes to sell – I assume he had a store, it got bombed, and he saved what he could to try to make some money.

I manage to find some popcorn in the market, and I take it ‘home’ to my family. We usually eat popcorn on movie nights. That’s another thing that has been stolen from me – will I ever sit with my family and eat popcorn while watching a movie again? The whole evening, I’m zoned out. It’s like my life has become the movie, but it’s a movie that should never have been made, a movie that I’d never watch but somehow find myself a leading character in. The innocent bystander. Is what’s happening even real? Is this my reality now?

One thing I like about myself is my ability to un-sync my head and my heart. Every day, my heart aches for the trauma and pain I see around me, and I want to cry, but my brain tells me that I don’t have time for that. I have to report on what’s happening; it’s the only way I can possibly help. So I tell my heart to pause, and I just listen to what my brain tells me to do.

And that’s what I do. Day after day after day. Autopilot. I continue to eat popcorn, sharing stories with my family about what I saw earlier today.

Excerpted from ‘The Eyes of Gaza: A Diary of Resilience’ by Plestia Alaqad, available now from Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2025 by Plestia Alaqad.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Zeteo.

Mehdi recently spoke to Plestia about her experience reporting on the Gaza genocide in real time. Watch below and check out other recent recommendations from Zeteo’s book club:

The world is watching.

Heart breaking. Please know that I, in the United States, read your article, because there are people here working to help stop a genocide. Because yes, that is what it is. I pray for your, your fellow journalists. I wish I could do more. I have a rage, a fury against, my country and it's ally.

A joke for a president with the devil whispering in his ear. I will keep you all, in my thoughts and I understand how hard it will be to find life after this insane genocide. All I have is the power to promise you I will never, ever stop thinking about you and what we did. Prayers. I am honored to read your story. The courage you have to stay and write it? Will be my example of humanity