Jesse Jackson Made It Possible for Democrats to Speak About Palestine

Activist James Zogby pays tribute to his late friend, who was the first politician to welcome Arab Americans into the Democratic Party - and even met with Yasser Arafat when others wouldn't.

Note from our Editor-in-Chief:

Rev. Jesse Jackson, a civil rights champion, died early Tuesday at the age of 84 after a long illness. Most mainstream media obits will tell you he ran twice for the White House and was a senior aide to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. What they won’t tell you about is his remarkable activism on Palestine at a time when the Palestinians had few friends in Washington DC. We asked his friend James Zogby, founder of the Arab American Institute, to tell that story.

-Mehdi

It was at a dinner in 1983 that Rev. Jesse Jackson came behind me, put his hands on my shoulders, and asked me to join his campaign for president. I turned to him and said, “I’ve been organizing my community of Arab Americans for the last four years, and I’m not sure I can leave what I’m doing.” He replied, “You will do more for your community in the next four months than you’ve done in the last four years.” He was right.

Until that point, Arab Americans had never been welcome in American politics as an ethnic constituency, mainly because of our support for Palestinian human rights. No campaign had ever included an Arab American committee. Candidates had rejected our contributions and endorsements. And no candidate had raised the issues that our community cared deeply about.

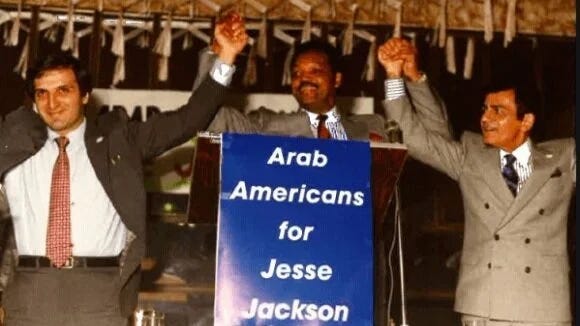

Rev. Jackson changed all that, and the response from Arab Americans was overwhelming. In fact, we were so moved by what we saw in his 1984 presidential campaign that we launched the Arab American Institute to focus on the lessons we had learned: increasing voter registration, encouraging candidate engagement, and the importance of bringing our concerns into the electoral arena.

Because Rev. Jackson had made it possible to speak about Palestine, we were able to build coalitions around the issue during the 1988 presidential campaign. Not only did we elect a record number of American delegates across the country, but we also built coalitions with Black, Latino, and progressive Jewish delegates, among others. We succeeded in passing resolutions in support of Palestinian rights at 10 state Democratic conventions. And by the time we got to the national convention in Atlanta, we had earned enough delegates to call for a minority plank on Palestinian rights.

It was in the late 1970s that I first began working with Rev. Jackson and helped arrange a visit to Palestine-Israel so that he could see the situation in the occupied lands for himself. The injustices he witnessed left him committed to addressing the centrality of Palestinian rights to Middle East peace.

In 1979, when then-US Ambassador to the UN Andrew Young was removed from his post because he had spoken with the Palestine Liberation Organization’s UN representative, many Black leaders, Rev. Jackson included, were outraged. He could not accept that the US had committed itself to a “no talk” policy with Palestinian leaders. He resolved to go to Beirut to meet directly with PLO chief Yasser Arafat in order to demonstrate, as he would say, that “a no-talk policy is no policy at all.” Before leaving, he addressed my Palestine Human Rights Campaign (PHRC) convention. His remarks, and his electrifying presence, drew international media coverage.

And then there was the 1988 Democratic Convention. Until then, there had never been a discussion about Palestine on the agenda. The campaign of the presumptive winner, Michael Dukakis, was adamant that the issue not be raised. In fact, Madeleine Albright, who was representing Dukakis, said if the “P word” was even mentioned at the convention, “all hell would break loose.” I warned them not to play “chicken little” with us and insisted that the issue be discussed.

Rev. Jackson chose me to present our plank from the podium of the convention. It was a heady experience to address the National Convention and introduce our position calling for “mutual recognition, territorial compromise, and self-determination for both Israelis and Palestinians.” My speech was preceded by a floor demonstration of more than 1,000 delegates carrying signs calling for Israeli-Palestinian peace and a two-state solution, and waving both Palestinian and UN flags. It was the first, and unfortunately, the last time that the issue was raised at a party convention.

The backlash was intense. While Rev. Jackson had secured a position for me on the Democratic National Committee, I was approached by party leaders who told me it would be best if I withdrew because my presence would only make me a target for Republicans and for some Jewish Democrats, who would use an Arab American in a leadership role at the DNC to attack Dukakis. Incoming party chair Ron Brown promised to make it up to us – and he did. He became the first party chair to host Arab Americans at party headquarters, to meet with Arab American Democrats around the country, and to address our national conventions. A few years into his term, he appointed me to fill a vacancy on the Democratic National Committee, where I’ve held a seat ever since.

In 1994, in the months after the signing of the Oslo Accords, Rev. Jackson accepted an invitation to be the keynote speaker at an international peace conference convened by Palestinians in Jerusalem. Once there, we were told by the Israelis that we could not meet in Jerusalem or hold a political meeting with Palestinians, but Rev. Jackson was determined to go forward. We spoke with Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Perez, urging them to allow the event to go forward. Even though they were unrelenting, Jackson convened the meeting and then announced that we would march from our hotel to Orient House, the headquarters for the Palestinians in the city. Israeli troops surrounded the hotel and told us we could not leave. True to form, Rev. Jackson announced that we would march anyway. We left the hotel and walked through the lines of Israeli soldiers.

To be honest, I was frightened – but also surprised by the power of his personality: Jackson’s presence was formidable on the world stage. Once the Israelis saw him leading this peaceful march right up to their blockade, they parted: Not only did they allow him to get through, but a large crowd gathered around him, wanting to shake his hand or asking to have their pictures taken with him. The Israeli commanders were furious. We marched to Orient House and had our meeting there.

In all the years I worked with Rev. Jackson, I saw not only his commitment to justice and his courage in the face of challenges, but the extent to which he recognized that his personal power could be used on the world stage to make a difference. I saw this as late as the 2016 Sanders campaign and the congressional victories of “the Squad,” beginning in 2018. He laid the groundwork for Democrats such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to take more pro-Palestinian positions today.

Jackson freed prisoners. He opened the doors to negotiations. He gave hope to the hopeless and a voice to the voiceless. He also challenged the Democratic Party to be principled and consistent in its commitment to human rights and justice. He will be missed, but his legacy lives on in the progressive movement for domestic and foreign policy change that he helped shape.

James Zogby is the president of the Arab American Institute, managing director of Zogby Research Services, and an alum of Jackson for President ‘84 & ‘88 and Sanders for President ‘16 & ‘20.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Zeteo.

Check out more from Zeteo:

Thank you for publishing this astonishing story of political courage. RIP, Rev Jackson. And thank you for opening doors for Arab Americans.

This is new history for me to learn; if only Kamala Harris had listened to Arab Americans /Palestinians and allowed them at her convention, things might be different now. I met Reverend Jackson once at O'Hare airport years ago because his wife wanted to pet my huge Standard Poodle. He seemed "larger than life" in person! Very tall with a commanding voice....RIP.