‘Treated Like an Animal’: How China Is Preventing Uyghur Muslim Women From Giving Birth

On Uyghur Genocide Recognition Day, Zeteo shares a harrowing story of forced sterilization and explores the wider physical and psychological toll on Ugyhur women in Xinjiang.

Zumrat Dawut, a Uyghur mother of three from China’s Xinjiang region, has spent much of her adult life haunted by the Chinese government’s repression against her community. After enduring months in a state-run concentration camp, she emerged only to face another trauma: the loss of her ability to bear children.

Four months after she was released from the concentration camp in the summer of 2018, she was told she would be forcefully sterilized.

“It’s my body part, but I wasn’t in control,” Dawut said seven years later after immigrating to the US.

Dawut is part of a Muslim majority ethnic group known as the Uyghurs, native to China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region, formerly known as East Turkestan.

Since as early as 2016, the Chinese government has been detaining Uyghurs in concentration camps it calls “vocational-education and training centers.” According to Human Rights Watch, Uyghurs were subjected to indoctrination, torture, and forced medical procedures. One hallmark of the government’s assault on Uyghurs is the prevention of births through forced sterilizations, forced abortions, and forced birth control, according to a UN report.

The Chinese government has repeatedly denied accusations of forced sterilization, calling these claims, including those of Dawut, “rumors and lies fabricated by anti-China forces.” The government also denies well-documented cases of abuse, claiming the training centers ensure “the basic rights of students participating in the training are not violated, and strictly prohibits personal insults and abuse of students in any way.”

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within a group constitutes genocide under the 1948 UN Genocide Convention. In 2021, the State Department called the persecution of Uyghurs a genocide, citing the forced prevention of births among other human rights abuses. Today marks Uyghur Genocide Recognition Day.

“For Uyghurs who have that predominantly Muslim identity, but also a very distinct culture and language, that is very difficult for the Chinese state to control,” said Julie Millsap, government relations manager for non-profit, No Business with Genocide. “Anything that can’t be controlled by the state is viewed as a threat.”

Woke Up in Pain and Alone

It is incredibly difficult to determine the exact number of Uyghur women who have been forcefully sterilized and the extent to which this torture is still being implemented today. A 2020 report from researcher Adrian Zenz analyzed Chinese government records to show the number of sterilizations specific counties in Xinjiang were aiming to achieve. In 2019, the Hotan City region was scheduled to administer 14,872 female sterilizations. In 2019, Pishan County planned to administer 8,064 female sterilizations.

Dawut said she got the news she was going to be sterilized while attending a flag-raising ceremony in the city of Urumqi in the Xinjiang province, a regular mandatory event for all former concentration camp detainees in order to pledge their loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party.

“They [Chinese authorities] say that there is an order in my neighborhood that 200 women should be sterilized,” Dawut said.

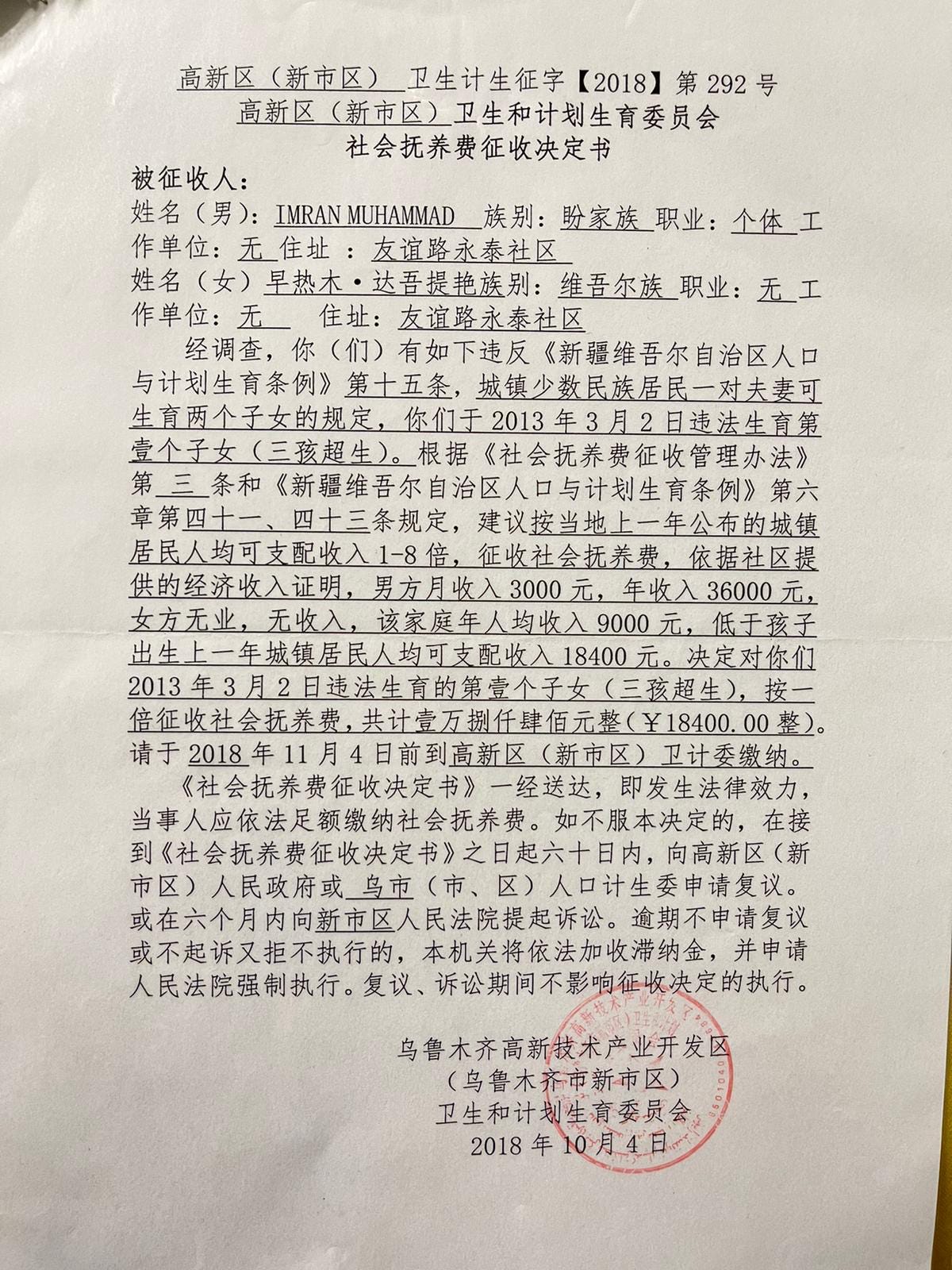

According to Dawut, authorities told her that any woman who had three or more children would be forcibly sterilized. The government previously fined Dawut 13,800 Chinese Yuan (nearly $2,000 today) for having what it deemed as too many children.

Dawut’s husband begged authorities not to sterilize her and offered to undergo sterilization himself. Dawut said Chinese officials refused because her Pakistani husband was considered a foreigner and not Uyghur.

“Every day they took five to six women from our neighborhood for sterilization, and they did not allow any family members to accompany the woman who’s going to be sterilized,” Dawut said.

Dawut woke up from the sterilization procedure in intense stomach pain, but was not provided painkillers. She was forced out of the recovery room after less than two hours and sent on a bus home alone.

That night, Dawut said she came home and begged her husband to help her get out of China.

“I’d rather live in the villages or deserts of Pakistan,” she told her husband. “I don’t care. I just don’t want to stay here.”

Dawut and her family received permission from the Chinese government to visit Pakistan, and from there fled to the United States in 2019, and sought asylum. The sterilization procedure still causes Dawut intense psychological distress.

An Enormous Psychological Toll

After Dawut first arrived in the US, she was still experiencing extreme abdominal pain. She went to a doctor for treatment and to examine whether it was possible to reverse the procedure. However, upon examining scans of her internal organs, doctors were shocked by how badly she had been mutilated.

“Mine [reproductive organs] was cut,” making the sterilization “irreversible,” Dawut said. “They [doctors] said I’d been treated like an animal.”

Doctors also found a tumor around Dawut’s uterus. She underwent a hysterectomy due to both the damage from the sterilization procedure and her cancer.

Dawut said the loss of her uterus and the prospect of not having more children seriously impacted her self-image and sense of womanhood.

“Mentally, I feel pressure because I don’t feel like I’m an ordinary woman that I should be,” she said. “I feel I’m not normal.”

Dawut, who had two girls and one boy, dreamt of having another son. Now 43 years old, she feels inadequate seeing pregnant women around her age. “I feel very sad seeing them, because they are exactly the same age as myself, but they are able to have children,” Dawut said.

The procedure had also impacted other aspects of Dawut’s life, like her sleep. She suffers from insomnia, and no treatment has helped. “I can’t sleep,” Dawut said. “I stay awake until 4am or 5am.”

When she is able to sleep, she frequently suffers from nightmares about her time in China. “Still, in my dreams I go back to my country, and police would chase me,” Dawut said.

Since she was released from the concentration camp, she engaged in acts of self-harm. This behavior increased in frequency after her hysterectomy.

“When I get upset… I start to slap myself very heavily,” Dawut said. “I just couldn’t control if I got upset or angry, I just stopped to slap myself.”

She has also suffered from suicidal thoughts. “I do have thoughts of killing myself,” Dawut said. “Thinking that if I just jumped into the sea, nobody would see me, and nobody could save me. I can just die.”

Dawut was interested in seeking mental health treatment, but was unable to afford therapy after she lost her health insurance. She was receiving Medicaid until her husband, the breadwinner for the family, began earning just enough money to not qualify.

Nur Aydin, a Uyghur psychologist based in Australia who has done pro-bono therapy for Uyghurs in different countries, said financial barriers are often overlooked when discussing Uyghurs’ lack of access to mental healthcare. “Therapy is expensive,” Aydin said. “I cannot, in good faith, say to someone who is struggling…you have to see me fortnightly and pay 200 plus dollars just to see me.”

Aydin said there is also a stigma around therapy that exists within the Uyghur community, largely as a reaction to the medical abuse and torture they faced in China.

“A mistrust regarding taking medicine and telling their deepest, darkest secrets to people that they do not know, that they cannot know if they can trust, is quite understandable,” Aydin explained. “I think it’s reasonable in that context.”

Aydin said China’s video and digital surveillance of every aspect of Uyghurs’ lives had a lasting impact on their psyche. According to reports from BBC and Human Rights Watch, Uyghurs could be interrogated for changes in behavior as small as not socializing with their neighbors as frequently or using the back door of their house instead of the front door.

“They don’t quite know what they’re allowed to do, what they’re not allowed to do, and what it then does to a psyche is people start to avoid normal behavior,” Aydin said.

‘One Strong Voice’

Uyghurs who’ve fled China often don’t have access to the same support systems that many victims of abuse have, like calling a loved one. Many Uyghurs are afraid that maintaining contact with loved ones still in China could lead to retaliation against them.

“You’re not allowed to call anyone, because everyone keeps telling you, do not contact me,” Aydin said.

Aydin warned that there is a danger for the Uyghur community in not addressing mental health issues. Adults struggling with their mental health have the potential to pass these problems down to their children. Aydin said people may also turn to alcohol or drugs as numbing agents to dissociate from their distress.

“We just start rolling the snowball, so something that could be treated, could be addressed, and healed in communal approaches, then becomes something that isolates you,” Aydin said. “You start to really make this problem bigger by avoiding it.”

For Dawut, she finds comfort in spending time with her children. She credits her husband for encouraging her kids to spend time with her after they came home from school each day.

“My husband told them that after school, after you come home, just to talk to your mom…take her out, whether you go to shopping centers, or just go for a walk to these kinds of green places,” Dawut said.

Dawut still hopes to get treatment for her mental health struggles and urges more people to speak out in support of the Uyghur community in dire need of care.

“I have given lots of sacrifice, but unfortunately, there are so many people still silent,” Dawut said. “I hope that everyone can be together in one strong voice and do more.”

This reporting was funded by a Pulitzer Center fellowship grant for reporting on mental well-being in the US. This story features an interview with Zumrat Dawut, translated by Zubayra Shamseden.

Khaleel Rahman is a freelance journalist and former talk show producer for Connecticut Public Radio. He also writes satire for The Onion and Reductress. Follow him @krahman333 on X.

Check out more from Zeteo:

Thank you for bringing attention to this horror. 💔

Thank you, thank you, thank you for bringing attention to the forgotten and overlooked Chinese genocide of the Uighur people and other indigenous ethnic groups in Xinjiang.

By the way, in 1951 it was reported that among the many brutal atrocities of the Chinese after Mao's conquest of Tibet was forced sterilization of women. Reference "In Exile from the Land of Snows", perhaps the best book ever written about the exile of the Dalai Lama, the concentration camps, the brutalization, and the continuing genocide of the Tibetan people. Tibet is where Mao and his acolytes honed their genocide skills to be later used in Xinjiang.