Why I Fled Trump's America

New Zeteo contributor and fascism expert Jason Stanley’s powerful essay on what growing up as a son of Holocaust survivors has taught him about the dark moment we’re witnessing today.

Note from our Editor-in-Chief:

Jason Stanley, a former professor of philosophy at Yale University and best-selling author of two books on fascism, has joined Zeteo as a new contributor. His provocative first piece for us, below, reveals why he has left the United States and Yale for Canada and the University of Toronto, and why he considers Israel's actions in Gaza a "permanent stain" on his religion. You won't always agree with everything Jason (or I) say – and that applies to all of our contributors here at Zeteo! – but our goal is to publish the world's leading thinkers and essayists, people who spark good-faith debates and discussions. Jason is certainly one of them. Jason's new piece is available in full to our paid subscribers, so if you haven’t already, please do upgrade from free to paid today to read the entire essay, and to help support independent journalism.

- Mehdi

In March 2025, I decided to depart the United States to move north to Canada, joining the faculty of the Munk School at the University of Toronto. I did not want to move from where I taught, at Yale University, or New York City, where I lived half the time. But what pushed me over the edge was Columbia University’s decision to agree to the Trump administration’s demands over charges of “antisemitism.” Columbia’s deal with the Trump regime threatened to be a model for the capitulation of American universities to fascism. Columbia’s decision was cowardly and, of course, ineffective, but it was in keeping with the university’s deference and cowardice in the face of backlash against supposed antisemitism; earlier in the year, Columbia forced Katherine Franke, one of its more distinguished faculty members in the law school, into “accelerated retirement” over comments on television about Columbia’s anti-war protests. Columbia’s decision this week to settle with the Trump administration for $200 million over allegations of antisemitism has only solidified my decision.

I am Jewish. My identity was formed by the experiences of my refugee parents. My father arrived in New York City from Berlin at the age of 6 on August 3, 1939, barely making it out of Germany before the war broke out, having experienced the horrors of Kristallnacht. Though my father came from a prominent German family, this did not protect him, nor did it protect the numerous non-Jewish Social Democratic opponents of the Nazis. I thus knew from an early age that fascism does not only come for the marginalized, it also (as we now are starting to see) comes for its better-placed scapegoats and opponents. My family history enabled me early on to recognize what was happening in the United States, and to narrate to myself a likely future path.

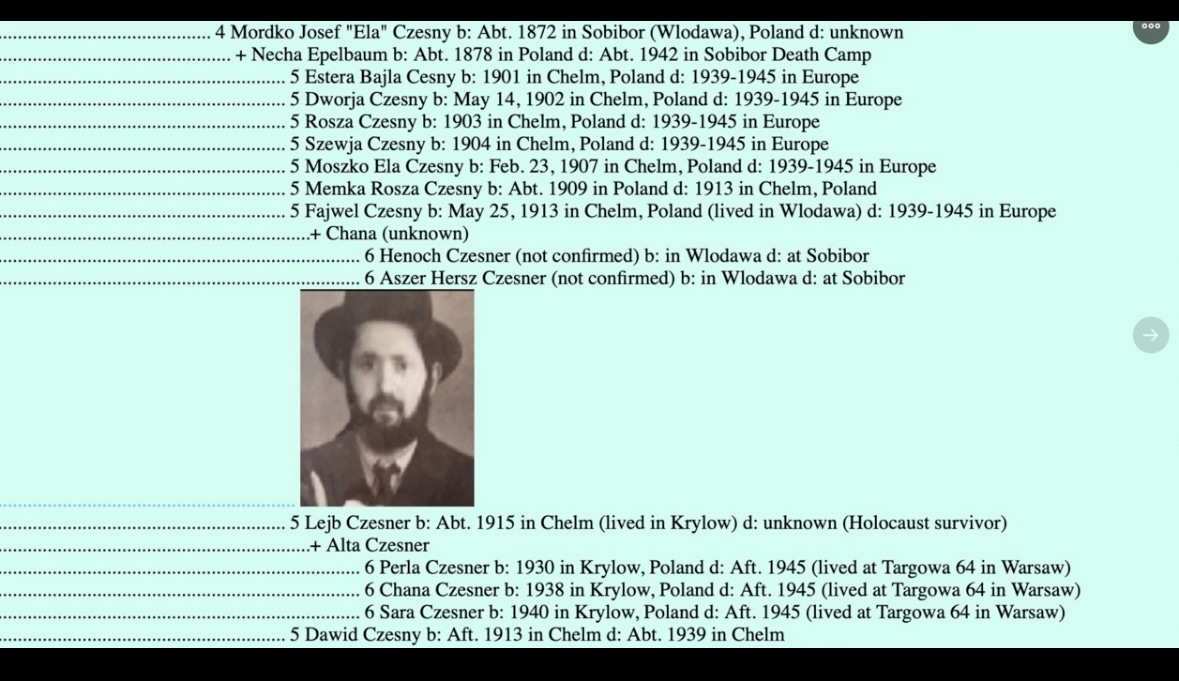

Unlike my father’s family, my mother’s family were always destitute peasants. My great-grandmother, Necha Epelbaum, orphaned at the age of 6, was married off before she was a teenager. After a life of hardscrabble poverty, she, along with six of her children and almost all of her grandchildren, was murdered by the Nazis (some, including her, in the gas chambers of the Sobibor death camp). My grandparents, Lejb and Alta Czesner, along with my mother and aunt, somehow managed to escape the fate of the rest of their family. In 1940, my heavily pregnant grandmother, my aunt, and my grandfather were deported by Stalin’s regime. My mother was born along the way. After five years in a Siberian labor camp, she was repatriated to Poland in 1945, where she met her father by accident on the train.

Post-war Warsaw was a terrible place for returning Jews. When my friend Marci Shore asked my mother if she missed the beauty of the Polish language, my mother reminisced about the frequency with which Poles on the streets of Warsaw would spit into her 8-year-old face.

All Jews have a history of oppression; for countless centuries, we were rendered second-class citizens and worse in Christian Europe. But my parents had deep trauma, which manifested in myriad ways. My father’s anxiety was so profound that I don’t recall him taking a single trip out of our home state during my entire childhood. The Holocaust impacted me indirectly, via my parents, and via the loss of almost my entire family. My Jewish identity is inextricably tied to my parents’ experience in Europe, and the fate of my family in the European Holocaust.

Because I am first and foremost my parents’ child, my closest felt bond is with other groups facing oppression because of who they are. As the German historian Harald Jähner has written, we Jews do not count those who were killed in World War II; we count those who survived.

When I hear Palestinians today speaking about the loss in their families, it is immediately familiar – the loss of homes, and the almost complete annihilation of individual families – that is the language I grew up hearing, and that is how I initially recognized, on a visceral level, before the academic scholarship, that we are witnessing a genocide. Today, it is the Palestinians who face the extermination we endured. Many American Jews, especially in younger generations, recognize this as well. By protesting Israel’s actions, they are defending my religion against a permanent stain.