I Love Pakistan. But With Rampant Cruelty in the Country, There’s Much To Mourn

As Pakistan celebrates 77 years of independence, it's time we acknowledge the rising abuse and endless governmental failures across the board.

In the massive, overburdened metropolis of Karachi, millions of ordinary citizens struggle to survive. The hardships are too numerous to list adequately: a fragile law and order system presided over by a mercenary police force, a corrupt provincial government growing fat and rich while impoverished citizens labor tirelessly for salaries that ought to be illegal in the 21st century with almost zero basic services provided to them – not healthcare, not education, not even potable water. Last April, two children in Karachi’s northern district of Nazimabad died from drinking water that was so polluted it was contaminated with worms “that could be seen with the naked eye.” Experts later classified the water as turbid, so filthy that even chlorine tablets were ineffective in rendering it drinkable.

Karachi, my hometown, is an urban mess run by gangsters and thugs if it runs at all. Cruelty is endemic to the city. Though it is an ethnically diverse city, more than any other in Pakistan, minorities have suffered here. A violent campaign saw Shia Muslims assassinated in the 1990s. Ethnic Pathans from Northern Pakistan or refugees from Afghanistan are often set upon by political parties even though they make up an integral part of the city and survive in neighborhoods without even the minimum of public services.

Such services are hard to come by, however, no matter where you live. Try to file a police report and experience humiliation at the hands of a notoriously corrupt force, try to survive the summer months – with temperatures easily cruising over 100 degrees with no electricity. K-electric, formerly the Karachi Electrical Supply Company, is one of the most incompetent and feckless companies nationwide. The amount of load-shedding is so obscene that large swaths of the city go without electricity for hours while continuing to receive astronomical bills. If you don’t have the money, you cannot pay for a generator. If you don’t have the means, you cannot afford the cost of a private water tanker and must forfeit running water at home too. It is a rough city.

We inherited a bloated civil bureaucracy from the British, and yet the only thing that the Karachi Municipal Corporation (KMC) seems to do with any enthusiasm or efficiency is poison stray dogs. District municipal authorities have killed hundreds of thousands of stray dogs over the years, even though a “fully fledged” provincial rabies control program exists. In 2021, Pakistan killed an estimated 50,000 dogs by poison alone. Photographs shared in newspapers showed hundreds of dog carcasses lined up on busy roads – a shocking image of savagery. The authorities' preferred method of what they call “dog culling’” is to leave parcels of poisoned food all over the city. As a result, stray dogs, starving and trying to feed their young, die horribly in full view of pedestrians: convulsing with pain, frothing at the mouth, and howling on the streets.

In all the years I lived in Karachi, I never saw KMC do anything capably – the garbage is piled sky high and ignored for months, the roads are horribly constructed, and there are no working sewage systems; there are barely any public spaces that are free and well looked after – the only one I can think of that’s free is the beach and it is certainly not well looked after, littered with garbage and the sand soggy with slicks of oil. Karachi traffic is notoriously terrifying and seemingly out of the control of city authorities. But they poison dogs with aplomb.

In December 2021, a KMC supervisor was arrested after a toddler picked up a poisoned sweet intended for a dog, ate it, and died. Five other children also ate the toxic sweets that the official was carrying with him to leave around the city and had to be hospitalized. “The fact that innocent children and animals have had to pay the price for the heartlessness and cruelty of adults is disgusting,” Ayesha Chundrigar, who founded Pakistan’s first and largest animal shelter, the ACF Animal Rescue, told VICE World News at the time.

For a long time, I was one of the many Karachiites who said, ‘Yes, it’s terrible so many animals are suffering but what about the people?’ We have to solve the problems people face before we can turn to the animals – there are shortages of cooking gas, overcrowded public hospitals often short on medicine, and millions of women across the country don’t have the ID cards that are required to vote because voting in Pakistan is not a right but a luxury: you have to pay for the ID card. This week, UNICEF officials announced that 98% of infants under 2 years old in Sindh, Pakistan’s southernmost province, are undernourished – a shocking statistic. But it has become increasingly hard to ignore that these are interconnected systems of degradation, abuse, and governmental ineptitude.

A Spate of Cruelty

I have thought a lot about cruelty over the last few months. There is seemingly no respite from it, no shelter from the constant barrage of news of violence, torture, and pain no matter what country’s newspaper you are reading.

None of this is unique to Pakistan, we live in a world of bottomless cruelty – from the war crimes being committed in broad daylight and live-streamed from Gaza, mobs lynching Muslims in India, fascists on the march across Europe, rioters trying to set fire to asylum seekers in England and beyond. Many in Pakistan will argue that for all the cruelty before them, they have no space to consider the violence done to animals. Others point out that animal welfare is an elite concern in the country. Yet it’s a well-established fact that psychopaths and serial killers don’t jump straight into their crimes – they begin by torturing animals. After animals, they move on to people. What does it mean then to live in a society where the torture of animals is so widespread?

In the past two months, Karachi, the provincial capital of Sindh, and other cities have seen a spate of horrific cases of animal cruelty. In early June, two men in the Liaqatabad neighborhood filmed a video exhorting a third man – Qasim, an impoverished cleaner – to throw a puppy off a balcony. The men hated dogs, saying they scared the local children, even though that puppy, small, and desperate with fear, could not have hurt anyone. Qasim allegedly did as he was asked. The puppy was flung off the balcony and died.

After their video went viral, public outcry saw the poorest of the three men arrested. Qasim cut a familiar figure to anyone with knowledge of Pakistan’s corrupt policing – the fall guy, the character without connections who always pays the price for the crimes of the more powerful. Asad and Talat, the two men whose idea it allegedly was to torture the dog were not initially touched by the police, but because of the infamy of their video, they were eventually forced to turn themselves in. A case was registered against all three men but in a city where you can kill a man and walk free with no reasonable worry that the law will follow you, the chances that they will be punished before the law is slim.

“People are becoming bolder because there are no laws holding them accountable.”

-Sarah Jahangir, director of CDRS Benji Project for Animal Welfare and Rescue

In the weeks that followed the Liaqatabad case, horror story after horror story captured Pakistan’s attention. In the barrack city of Rawalpindi, a donkey’s ears were severed, the victim of an argument over land between two farmers. In Hyderabad, about 124 miles from Karachi, a donkey cart rider allegedly broke his donkey’s legs and mutilated its private parts in a fit of anger. And in Sanghar, upper Sindh, a landlord allegedly amputated the leg of a camel belonging to a poor farmer after it strayed onto his land to forage. The landlord has not been arrested because the police can find “no evidence” against him. The man who owned the young camel, only 8 months old when its leg was hacked off with an axe, declined to identify the landlord to the police. Thanks once more to social media scandal and public anger, the police were forced to act. But not having the remit to arrest a landlord – a powerful figure in Sindh’s agricultural heartland – they filed what’s known as a first information report against “unknown persons.” Eventually, they arrested six local men who denied having anything to do with the crime.

A Warning Sign

The horror with which animals are treated in Pakistani society is emblematic of an undercurrent of rage that always existed but seems to have spread dangerously in the post-pandemic years, a warning sign of the fury and alienation that lurks barely under the surface.

Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky said that “the degree of a civilization can be judged by its prisons,” but he might have included how its animals are treated. Animal shelters throughout Karachi are flooded with cases of torture inflicted on dogs, donkeys, and other small animals. And while Karachi Zoo takes in ticket fees every day from visitors, its animals are starved and locked in empty, filthy cages and staff members are often denied their salaries for months.

“People are becoming bolder because there are no laws holding them accountable,” said Sarah Jahangir, the director of CDRS Benji Project for Animal Welfare and Rescue, a shelter in Karachi that took in both the donkey with the broken legs and the camel with the amputated leg.

The young camel is being looked after at CDRS where they are managing her infection and pain and working with the livestock department on a bionic solution that would enable her to stand again, critical to her health and survival. But the donkey’s chances of surviving were quite low, Jahangir told me when we spoke in July. “It’s a daily thing we see,” she continued, referring to the cases of abuse. “It’s getting worse and without harsh laws, people think ‘we can get away with murder’ because they literally can.” Days after I spoke to Jahangir, the donkey died.

ACF Animal Rescue’s Chundrigar is working on exactly that. She worked with a law firm to put together a several thousand-page brief on animal rights laws from around the world, including Nepal, Turkey, and various Western countries, which presented the document to the Sindh Chief Minister. “It’s 2024 and Pakistan is still without active animal rights laws,” she told me, underscoring that “prioritizing the most vulnerable” benefits everyone in a society because it can only foster compassion. To her point, Chundrigar’s shelter, which has rescued and helped more than 35,000 animals also runs workshops for donkey cart drivers and local children, and goes into bazaars that sell and trade animals in the hope of educating and supporting those who work with animals.

“One day, I saw a young man, in his twenties, cross a double main road, his hands full of mud,” Chundrigar said. “I was curious and worried about how he would cross safely with the crazy traffic.” While she was watching him, concerned that he would get walloped by a motorcyclist or a speeding truck, Chundrigar noticed the man march towards a clay bowl that some good Samaritan had left out filled with water for birds to drink from in the scorching Karachi heat. “He dumped all the mud in his hands inside the clean water as the pigeons were drinking,” Chundrigar recounted, “and started laughing when they began flapping their wings in distress.” People are uncomfortable when animals are in their natural, tranquil state, she concluded, they seem to relax only once the animal struggles and suffers.

Pakistan this week marked 77 years of independence. For those of us who love Pakistan, there is much to mourn. The pervasive cases of animal cruelty also reflect the contempt and destruction with which we treat our natural heritage. In May, a rare Indus Blind Dolphin was killed in Sindh apparently for fun; again a video circulated over the internet. Bulhan, as the dolphin is known locally, is one of the two surviving river dolphin species in the world that date back to creatures that swam the waters of this region 50 million years ago. There are six species of river dolphin in existence today, ours is the only blind one. A striped Hyena was recently killed in Balochistan. The International Union of Conservation of Nature lists the animal as near threatened; Bulhan is on its red list of endangered species. Senior WWF officials warned in July that Pakistan’s already critically endangered leopard population is at risk of vanishing entirely and the reason is unsurprising: the beautiful, rare leopards cannot survive their high rate of encounters with humans. We are destroying their forest cover, we are hunting them illegally for our shallow entertainment, we kill for fun, for sport. We are the plague.

“Nothing and No One Is Spared”

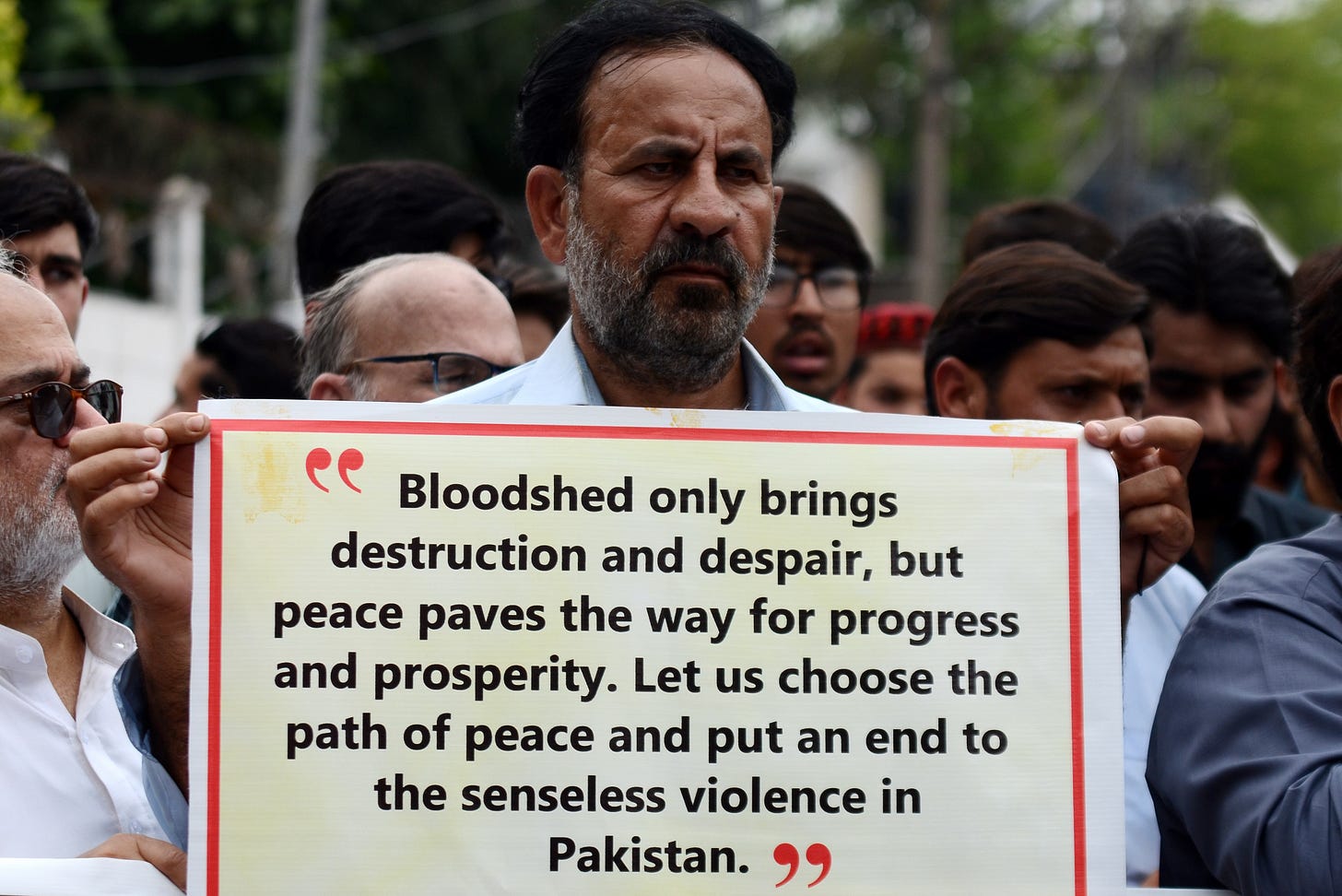

The issue of cruelty on a micro level exists against a backdrop of very serious political crises. As I was writing this piece, I had to pause repeatedly to update it with newer cases of violence and cruelty – not just against animals but people as well. A spate of violence in the Shia-majority town of Parachinar in northern Pakistan saw at least 50 people killed by Sunni tribesmen and more than 200 wounded. Baloch protesters calling for the release of their leaders from prisons and demanding answers about the many cases of disappearances were arrested by security services. The government blocked highways to quell the protests and cracked down on the activists.

A man in the northern town of Swat was burned alive by a mob after being accused of blasphemy. Pakistan’s blasphemy laws are so deadly that even mentioning the crime of an accused person can count as blasphemy. In any event, mobs do not need just cause to take the law into their hands, a mere accusation is enough and so charges of blasphemy are often used to settle petty enmities and grudges. The man was in police custody, already apprehended for his alleged crime, when he was killed. The mob beat him with a hammer, in the very presence of the institution that was supposed to protect him. After his murder, the man’s mother was forced to publicly disown him to keep herself and her other children safe. This was not a unique case. Another man in Sarghoda was lynched and killed in May on similar charges.

The mobs have little true understanding of Islam, they are armed with fury, not scripture. In the same way, those who have tortured animals with the belief that the only life that is sacred is their own, know very little about what their religion believes about the sanctity of all life. There is an understanding in Islam that animals are, as we are, conscious of God. No matter that they cannot bend in supplication, in their being, creation, and beauty they are proof of the divine. As such, Islam forbids the killing of animals except for food or in the case where the animal has attacked a human and the violence is justified by defense. The Quran describes enemies of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) as men “who strive throughout the land to cause corruption therein and destroy crops and animals.” The hadiths, stories of the Prophet’s life and actions recounted by his followers and close associates, are filled with accounts of the Prophet Muhammad protecting and nurturing animals and of God’s forgiveness to those who showed mercy to helpless creatures, including the story of a prostitute who noticed a dog panting out of desperate thirst. She went to a well and using her shoe drew water for the dog to drink from, an act of compassion that redeemed her enough for God to forgive her of all her sins.

Pakistan is often spoken of as a country with a bottomless reserve of resilience. It would need it to weather its constant political storms. But this epidemic of cruelty forecasts something ominous and deep. “It is a sign of a society where nothing and no one is spared abuse,” as the Pakistani author, Rafia Zakaria, wrote after this ominous rash of abuse cases.

In July, 20-year-old mother Sania Zehra was discovered hanging from a ceiling fan in her home in Multan. She was pregnant with her second child. Sania’s husband beat her, relatives say, and threatened her with violence if she did not sell a property and hand him the money. Though the forensic doctor present on the scene when her body was discovered noted her bruised eyes and her broken jaw, pressure allegedly applied to the Punjab police from somewhere has resulted in the narrative around this young woman’s grisly death morphing until it sounded like a different case altogether. She wasn’t pregnant, wasn’t beaten, wasn’t asphyxiated, and, according to her husband’s family, had committed suicide. Sania’s family strongly contested the claim and after convening a committee comprised of experts to look into the case, the Punjab Information Minister declared the case a homicide and accused Sania’s mother-in-law and husband of acting together to fake a claim of suicide.

This month in Sindh, 22-year-old Sobia Batool Shah was sleeping when her father and other male relatives attacked her with a hatchet. They were angry that she was insisting on divorcing her husband – Islam has the most liberal divorce rights for women of any religion; in Pakistan, a woman need only select the right of divorce on her wedding papers and she can file for divorce whenever she wants. Sobia had been threatened by her father previously and she had gone to the courts for protection. They did nothing, suggesting she go live in a women’s shelter.

Who will give Sania and Sobia justice in a country that’s ranked second to last in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap 2024 report? The police force that changes facts by the day? Will the courts that have failed sitting prime ministers be dedicated enough to devote themselves to the trials of ordinary men and women? It is unlikely. Till then, Sania’s father posted about the case on his Facebook, and Sobia, defiant in a hospital where she is being treated for her injuries, has finally been given police protection. Though her father was arrested, her brother is out on bail. “I am very scared,” she told the press.

Miss previous editions of Fatima Bhutto’s ‘The Global South’? Read them here, and be sure to subscribe and select ‘The Global South’ to get the column in your inbox every month.

If you haven’t already, please do take two minutes to fill out our first survey. We really value your feedback, especially as we continue to grow!

CLICK HERE TO FILL OUT ZETEO’S SUBSCRIBER SURVEY

A very well written article. Author should have once mentioned the Bhutto family and cohorts ruling the Sindh province for last 5 decades.

Fatima Bhutto's love for her country, and her devotion to the true essence of Islam, make this story all the more heartbreaking.

Her description of the perversion of Islam makes me reflect on the Christian right's fascist, zionist, perversion of the teachings of Jesus. Christianity, Islam, Judaism, all have in their original sources and essences, beauty, mystery, wisdom, but the perversions of these faiths is what makes me allergic to organized religion.